- Home

- Our Work

- Stirling's Story

- Blog

- Women in Construction at Bannockburn House

- Avenues to the Past: Stirling’s Historic Streets Exhibition

- Stirling Business Awards 2025

- What is a Conservation Area

- 20 Great Buildings of Stirling

- Reminiscence Art Project

- On the European Stage: Preserving by Maintaining conference, Bratislava

- The Abolition Movement in Stirling

- Practical Workshop on Retrofitting Insulation with A. Proctor Group

- Walker Family Visit

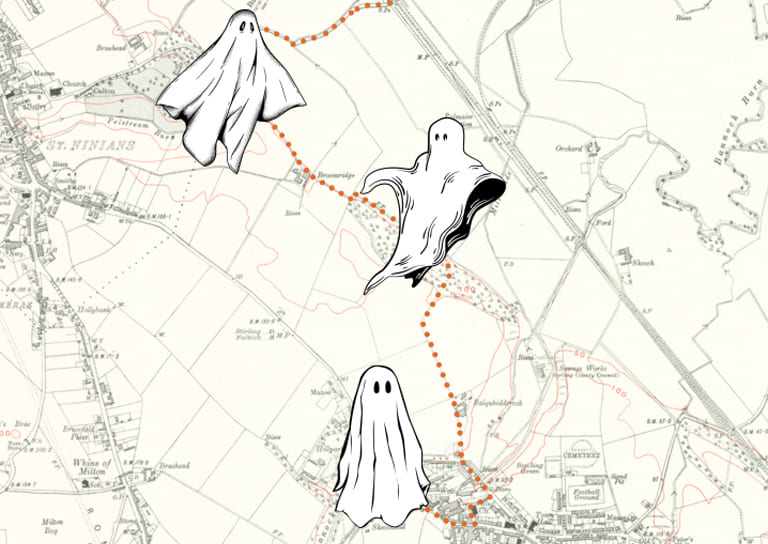

- Ghost Tales from Stirling

- Snowdon House and The West Indies

- Stirling’s Streetscape Stories: Photography Workshop

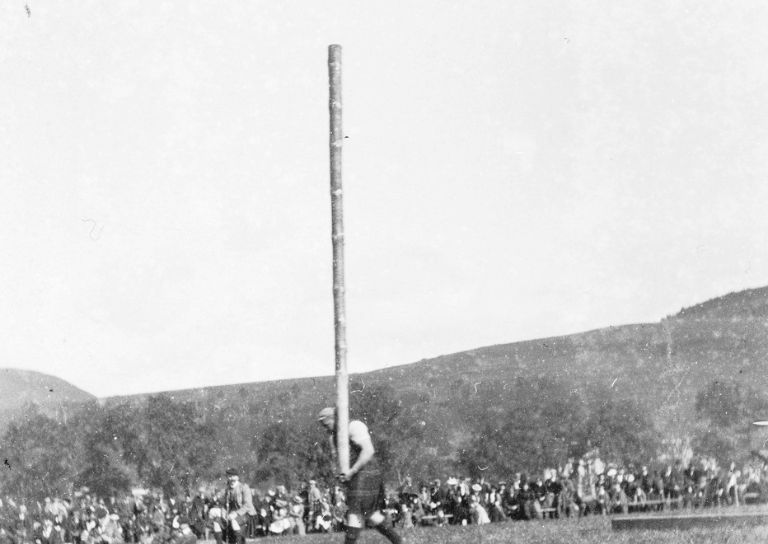

- Stirlingshire’s Highland Games

- Creative careers in the heritage sector

- Postcards From Stirling

- Stirling’s Gala Days

- Building Surveying Student Intern at Stirling City Heritage Trust

- Heritage Trail: Stirling Walks

- Local History Resources

- Stirling Through the Decades

- Stirling’s STEM Pioneers

- Traditional Skills: Signwriting

- Christian MacLagan, a pioneering lady, but born too soon?

- Traditional Shopfronts in Stirling

- Stirling History Books for World Book Day

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Joe Hall

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Lindsay Lennie

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Andy McEwan

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Pam McNicol

- Celebrating John Allan: A Man of Original Ideas

- The Tale of the Stirling Wolf

- Stirling: city of culture

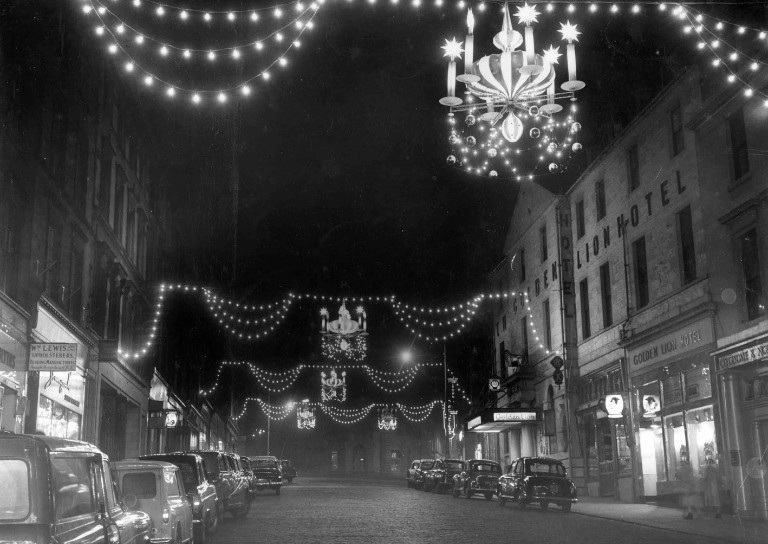

- Christmases Past in Stirling

- Stirling’s Historic Graveyards

- Top 10 Tips for Architectural Photography

- An Interview with David Galletly

- Springtime in Stirling

- The Kings Knot – a history

- A Future in Traditional Skills

- Robert Burns’ First Trip to Stirling

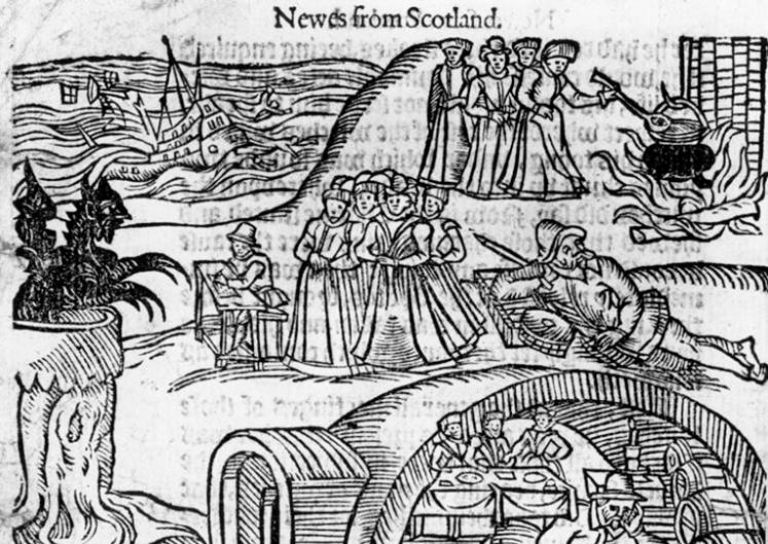

- Stirling’s Witches

- Stirling’s Ancient Wells

- An architecture student’s take on the City Of Stirling

- Ronald Walker: Stirling’s Architect

- Stirling’s Statues

- Stirling’s Wee Bungalow Shops

- Stirling’s Historic Hospitals

- Women in Digital Innovation and Construction

- Heritage at home: 8 of the best online heritage resources

- Stirling featured at virtual heritage conference

- Five of Stirling’s greatest John Allan buildings

- Women in Construction – Stirling event report

- Scotland’s trailblazing women architects

- Stirling’s Heritage: Spotlight on The Granary

- TBHC Scheme now open to properties in Dunblane and Blairlogie

- How drones help us inspect traditional buildings

- Hazardous Masonry & Masonry Falls

- Mason Bees: What’s the Buzz?

- Stirling Traditional Skills Demonstration Day Success!

- Floating Head Sculpture at Garden Glasgow Festival 1988

- The story behind Paisley Abbey’s Alien gargoyle

- Cambuskenneth Abbey

- Stirling City Heritage Trust Publications

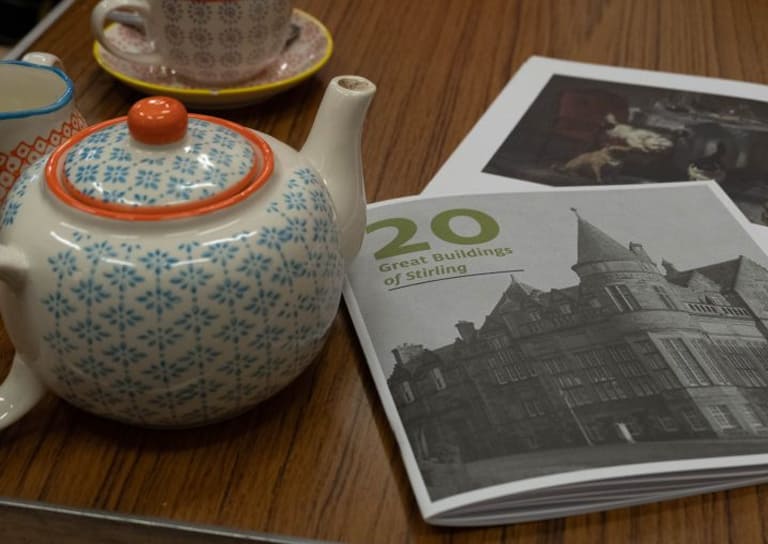

- Sharing Memories: Taking '20 Great Buildings of Stirling' into the community

- William Wallace Statues In Stirling

- Coronations and Royal Christenings in Stirling

- The development of King's Park

- Energy efficiency project awarded grant from Shared Prosperity Fund

- Inspiring the Future: Stirling City Heritage Trust's Women in Construction Event at Wallace High

- Doors Open Days Talk: Who Built Stirling?

- 10 Years of the Traditional Buildings Health Check

- Growing up in Stirling: A Night of Reminiscence at The Smith

- SCHT visit to Brucefield Estate, Forestmill, Clackmannanshire

- Statement on Christie Clock

- Stirling’s Lost Skating Heritage

- Laurelhill House and the West Indies

- Beechwood House and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings

- Building Resilience: Maintaining Traditional Buildings

- Shopping Arcades

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Fabric First

- Stirling Reminiscence Box

- Level 3 Award in Energy Efficiency for Older and Traditional Buildings Retrofit Course (2 Day)

- New Retrofit Service now available for Traditional Buildings Health Check Members

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Windows

- Architects and The Thistle Property Trust

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Insulation

- Stirling City Heritage Trust at 20

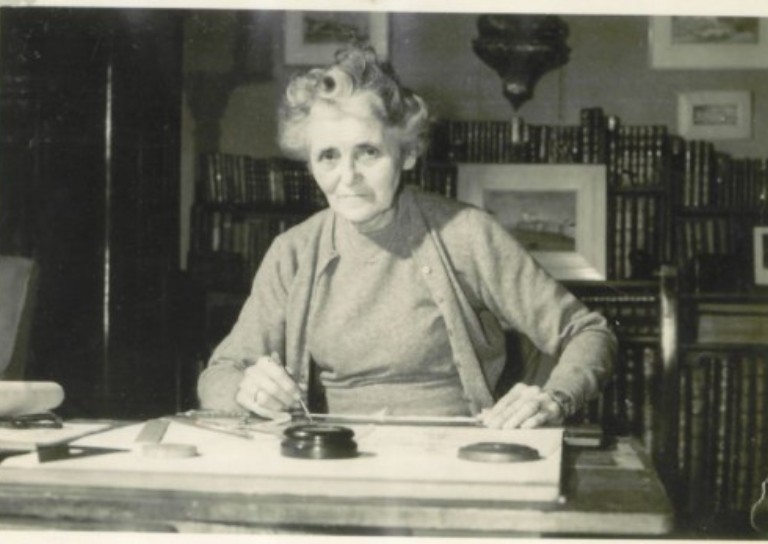

- Miss Curror and the Thistle Property Trust

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Chimneys

- Statement on Langgarth House

- World Heritage Day: Exploring Hayford Mill

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Climatic Adaptation

- SCHT 20: Championing Women in Construction

- Guest Blog: Dementia Friendly Heritage Interpretation

- Community Consultation launched for Stirling’s Heritage Strategy

- Stirling's Lost Swimming Pools

- SCHT Grant Conditions: Owners Associations

- Kings, Wolves and Drones: 20 years of care and repair at Stirling City Heritage Trust

- SVE Inspire Awards September 2024

- Women in Construction at Bannockburn House

- About Us

- Support Us

- Contact

Architects and The Thistle Property Trust

John Allan & Social Reform

In 19th century Stirling, several prominent architects emerged and shaped the architecture of the burgh, including John Allan, who had moved from Fife in 1870. Living at the Top of the Town, he became an advocate for housing improvement and social reform. Around 1883, he published A Practical Guide on Healthy Houses and Sanitary Reform, written to be “available for all classes”. He believed that physical and mental health went hand-in-hand with improved and affordable housing for all.

There are dwellings in Stirling, where in these days of cruelty to animals is forbidden, no-one would house a dog, or a horse, if he wished to maintain its health. Fancy infants born, dying and bred up under such conditions? (Letter from John Allan to Stirling Observer, Saturday 17 Jan.1914)

You can find out more about John Allan and his work by downloading our publication on Allan, John Allan: A Man of Original Ideas, or visiting our online exhibition.

The Thistle Property Trust and Eric S. Bell

The Top of the Town’s decline began as far back as 1603, when King James VI of Scotland was also crowned King James I of England. He promised to return to Scotland every three years after his coronation at Westminster, but he only returned once before his death in 1625. Without a monarch and a court, the wealthy noble residents of the Top of the Town departed, but the population of Stirling continued to increase as Scotland became more industrialised. The top of the town’s once grand buildings were then subdivided into housing for the city’s workers.

In the 19th century new green suburbs with wide streets were being created for Stirling’s middle-classes, and tenements and cottages were built for the less wealthy. Stirling was advertised as a healthy alternative to living in smoggy cities like Glasgow and Edinburgh, and travel across Scotland became much easier when a railway station was opened in Stirling in 1848. Despite the increasing wealth of Stirling’s middle classes, the conditions in the Top of the Town worsened. By the 1920s, the medieval buildings were crumbling after years of neglect and the area had become a densely populated slum.

On 7th December 1928, Scotland’s first property trust was formed in Stirling. The Thistle Property Trust (TPT) purchased and refurbished the historic buildings in the Top of the Town area to provide decent and affordable family homes. The driving force behind the TPT was the Stirling branch of the National Council of Women, which was founded in 1895 in response to poor working conditions for women at the time. The TPT also created allotments in the St John Street area and installed a merry-go-round for local children. In a future blog post we’ll find out more about the pioneering women who established and ran the TPT.

The TPT were selective; they did not “take over any and every property”, it had to be “bad enough to need overhauling” and also “good enough to be worth the effort.” The TPT believed that “such old property when rendered sanitary is better that any new ‘flimsy’ which can be offered as an alternative”, as the traditional buildings were “stronger, less liable to be damaged”, cheaper than constructing new housing, and more convenient as they were located nearer to their tenants’ work. (Excerpts from The Scotsman, Monday 29 April, 1929, “New Housing Crusade in Stirling”)

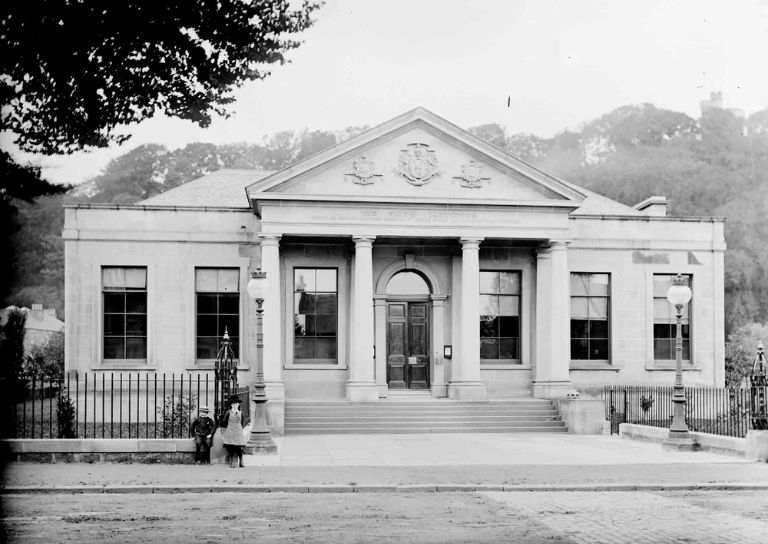

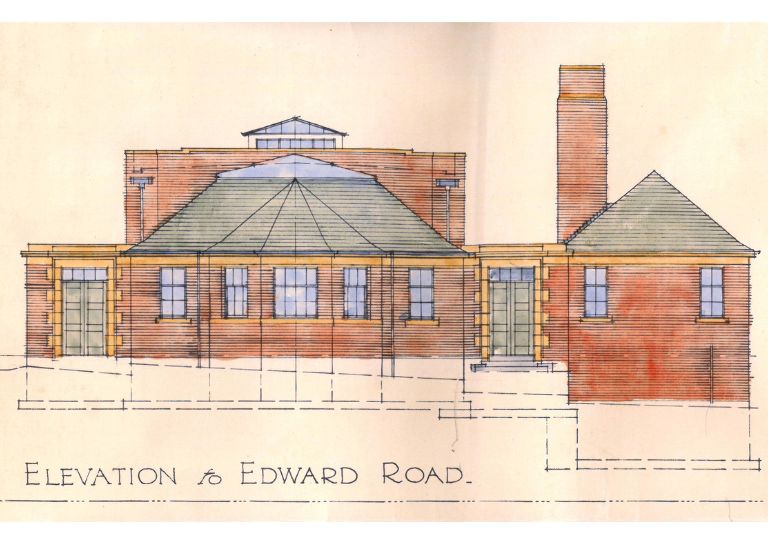

By 1933, the TPT had reconditioned an impressive 44 houses, housing 55 people. At this point, many inhabitants of the Top of the Town were moving out to newly built council housing, some of which were designed by Eric S. Bell, who was also the TPT’s architect.

Born in 1884 in Warrington, Bell’s father was Colonel William Bell of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, who had been stationed at Stirling Castle since 1881. In 1903, Eric S. Bell was working for Glasgow architects John Burnet & Son whilst studying at Glasgow School of Art and, during the First World War, he served as Captain in the Gordon Highlanders. Post-war, Bell began practicing as an architect in Stirling, becoming the architect for the TPT as well as the first President of the Stirling Society of Architects. He was also a Trustee of The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum. He died at his home in Stirling in 1973 and fittingly, he was buried in the Valley Cemetery in the Top of the Town.

You can find out more about the modern ‘Scotstyle’ social housing being designed by architects including Eric S. Bell via this Stirling Archives blog post: Homes fit for heroes - Raploch Housing plans, 1937 (stirlingarchives.scot)

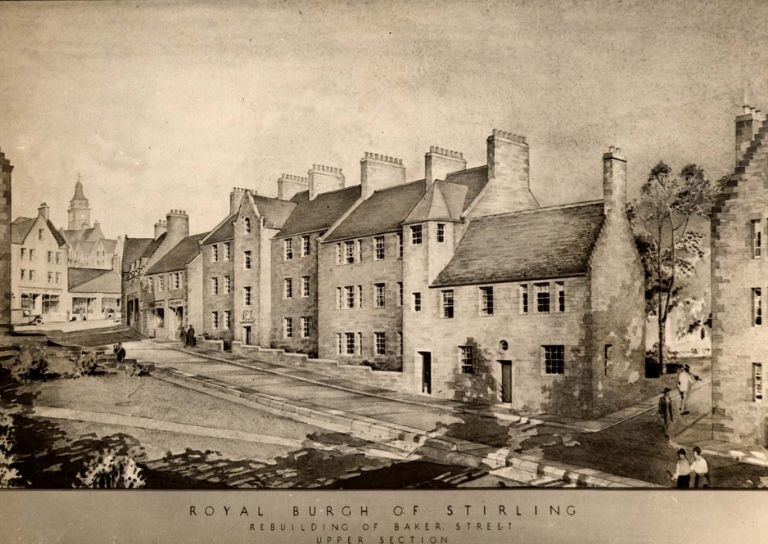

Frank Mears

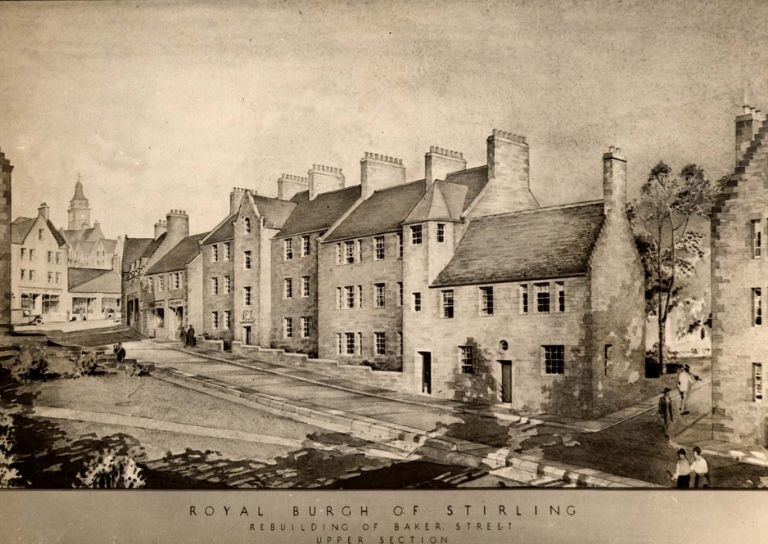

Despite the enormous efforts made by the TPT, Stirling Burgh made a compulsory purchase of a large number of properties in the Top of the Town. Sir Frank Mears, an innovative town planner, was responsible for the redevelopment of the Top of the Town between 1936-1953. He aspired to create modern cities which retained and conserved significant buildings, with sympathetic design and materials to be used in new buildings within historic areas. Mears was inspired by his Father-in-Law, Patrick Geddes, whose work in Town Planning in Edinburgh made him internationally renowned. Mears’ designs were completed by his partner Robert Naismith and Stirling Burgh Architect Walter Gillespie after Frank Mears death in 1953. Mears created plans for new housing to replace the demolished buildings, following the lines of the earlier streets. His designs also incorporated vernacular features like crow- stepped and Dutch Gables, and used traditional materials such as slate.

Whilst the work carried out by Frank Mears and his colleagues in the middle of the 20th century was pioneering, the approach taken would differ from current planning ideas. If it was designed today, an area like this would have more mixed-use commercial units on the ground floor, as well as more public green spaces.

Stay tuned for our blog post on the women who ran the Thistle Property Trust.