- Home

- Our Work

- Stirling's Story

- Blog

- Beechwood House and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- New Retrofit Service now available for Traditional Buildings Health Check Members

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Chimneys

- SCHT 20: Championing Women in Construction

- Stirling's Lost Swimming Pools

- Women in Construction at Bannockburn House

- Avenues to the Past: Stirling’s Historic Streets Exhibition

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Windows

- Statement on Langgarth House

- Guest Blog: Dementia Friendly Heritage Interpretation

- SCHT Grant Conditions: Owners Associations

- Stirling Business Awards 2025

- What is a Conservation Area

- 20 Great Buildings of Stirling

- Building Resilience: Maintaining Traditional Buildings

- Architects and The Thistle Property Trust

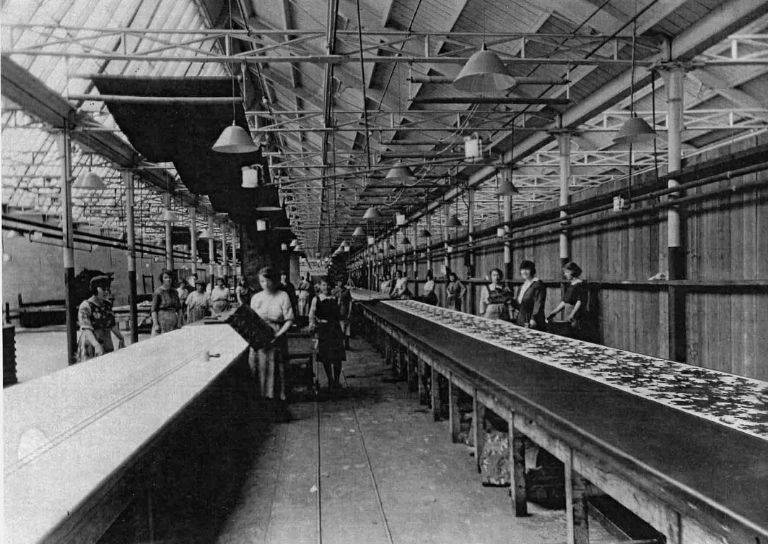

- World Heritage Day: Exploring Hayford Mill

- Community Consultation launched for Stirling’s Heritage Strategy

- SVE Inspire Awards September 2024

- Reminiscence Art Project

- On the European Stage: Preserving by Maintaining conference, Bratislava

- The Abolition Movement in Stirling

- Shopping Arcades

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Insulation

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Climatic Adaptation

- Kings, Wolves and Drones: 20 years of care and repair at Stirling City Heritage Trust

- Practical Workshop on Retrofitting Insulation with A. Proctor Group

- Marking the 80th anniversary of VE Day

- Walker Family Visit

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Fabric First

- Supporting traditional building repair in Stirling

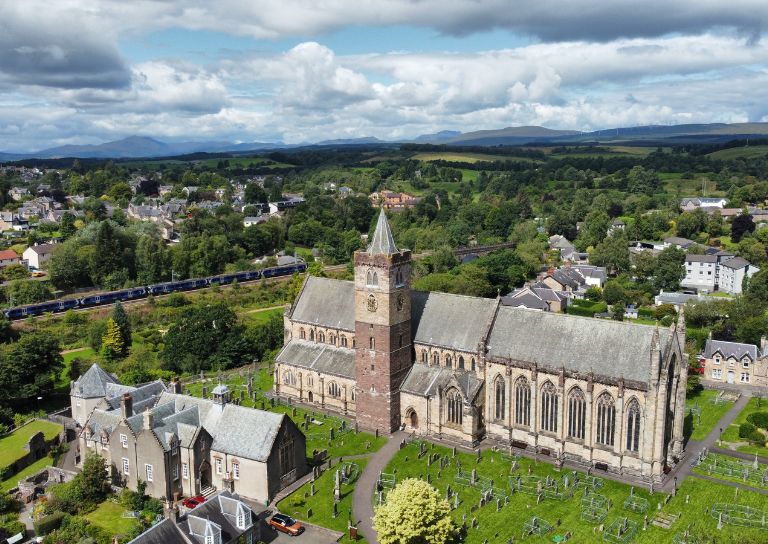

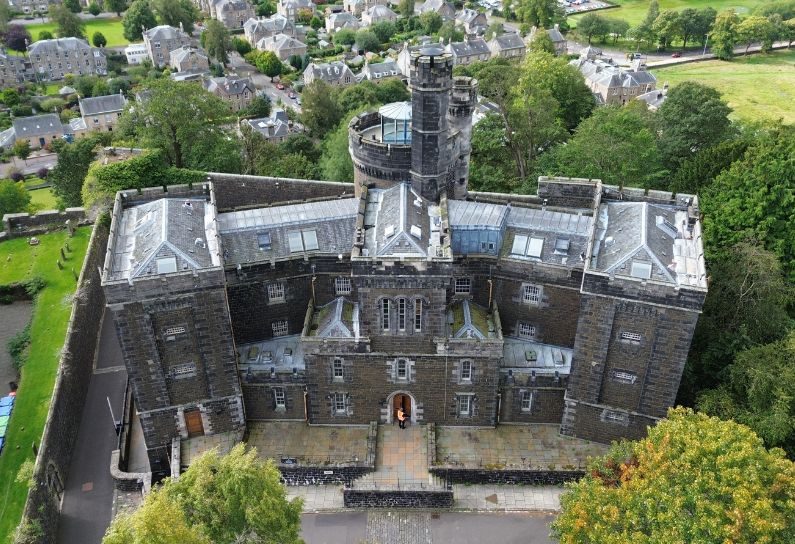

- Stirling's Historic Jails

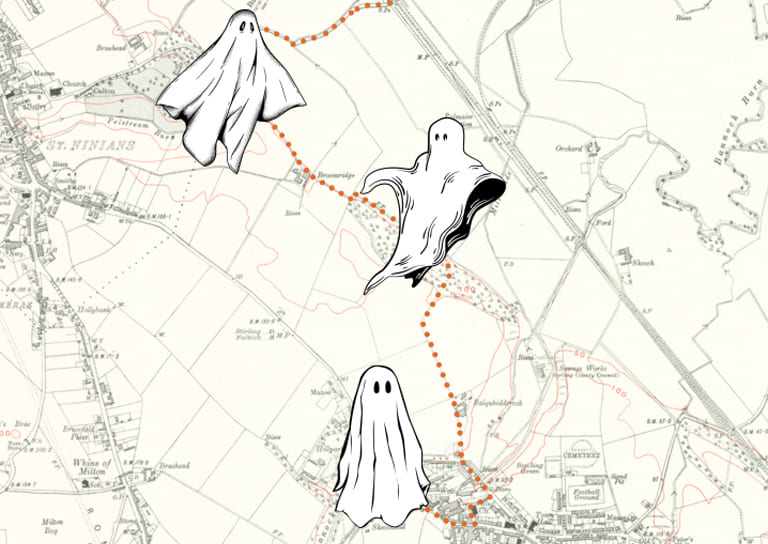

- Ghost Tales from Stirling

- Stirling Reminiscence Box

- Stirling City Heritage Trust at 20

- Retrofit Event: Meet the Suppliers

- Snowdon House and The West Indies

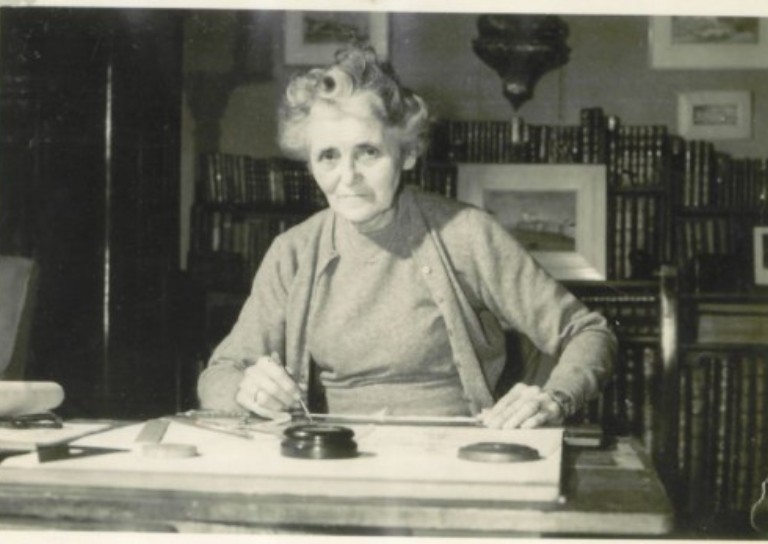

- Miss Curror and the Thistle Property Trust

- Dr Lindsay Lennie retires from Stirling City Heritage Trust

- Stirling’s Streetscape Stories: Photography Workshop

- Level 3 Award in Energy Efficiency for Older and Traditional Buildings Retrofit Course (2 Day)

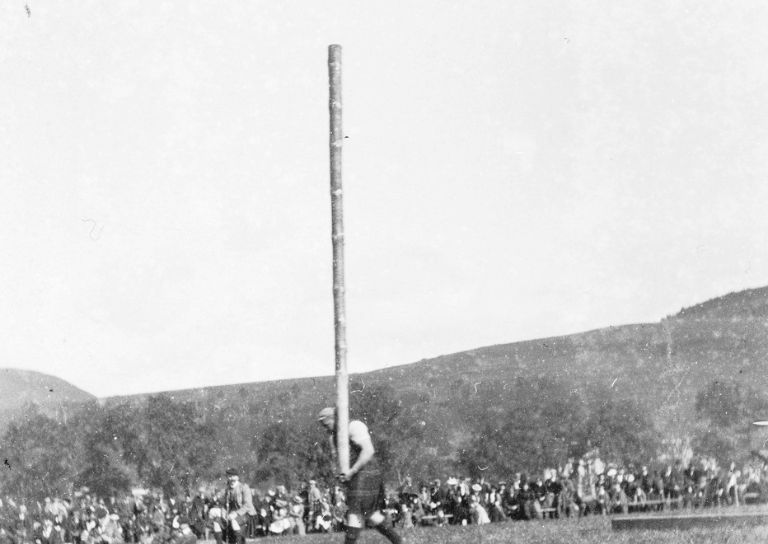

- Stirlingshire’s Highland Games

- Creative careers in the heritage sector

- Postcards From Stirling

- Stirling’s Gala Days

- Building Surveying Student Intern at Stirling City Heritage Trust

- Heritage Trail: Stirling Walks

- Local History Resources

- Stirling Through the Decades

- Stirling’s STEM Pioneers

- Traditional Skills: Signwriting

- Christian MacLagan, a pioneering lady, but born too soon?

- Traditional Shopfronts in Stirling

- Stirling History Books for World Book Day

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Joe Hall

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Lindsay Lennie

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Andy McEwan

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Pam McNicol

- Celebrating John Allan: A Man of Original Ideas

- The Tale of the Stirling Wolf

- Stirling: city of culture

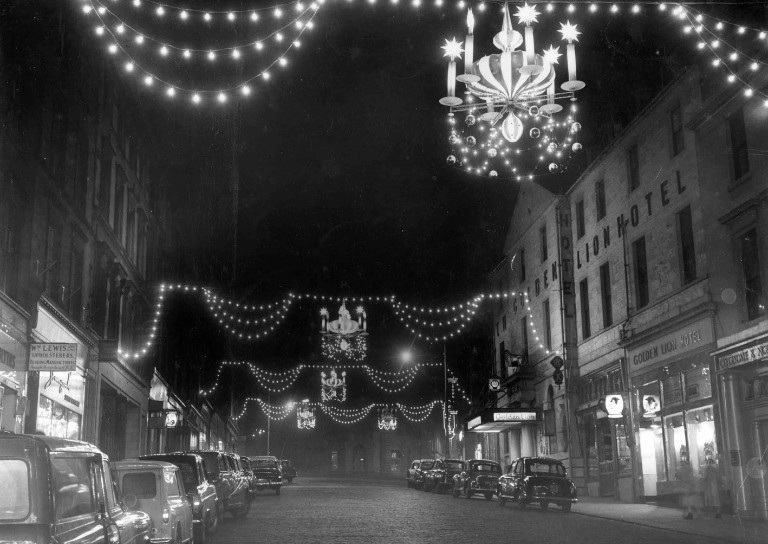

- Christmases Past in Stirling

- Stirling’s Historic Graveyards

- Top 10 Tips for Architectural Photography

- An Interview with David Galletly

- Springtime in Stirling

- The Kings Knot – a history

- A Future in Traditional Skills

- Robert Burns’ First Trip to Stirling

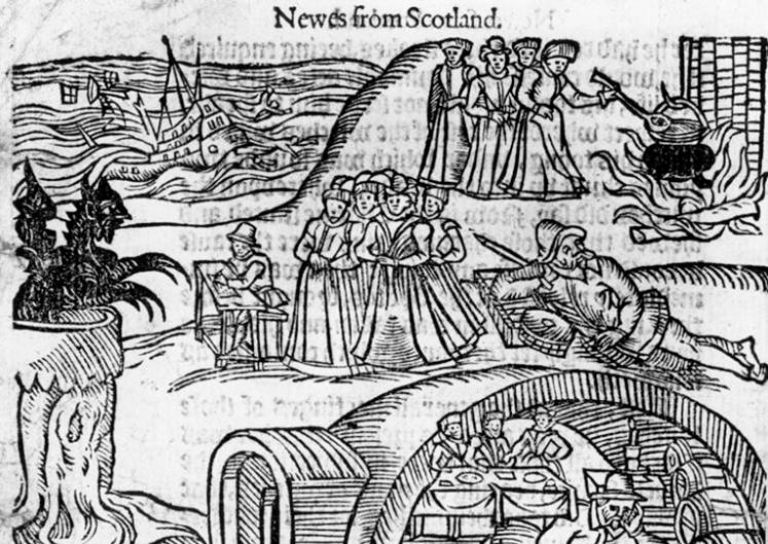

- Stirling’s Witches

- Stirling’s Ancient Wells

- An architecture student’s take on the City Of Stirling

- Ronald Walker: Stirling’s Architect

- Stirling’s Statues

- Stirling’s Wee Bungalow Shops

- Stirling’s Historic Hospitals

- Women in Digital Innovation and Construction

- Heritage at home: 8 of the best online heritage resources

- Stirling featured at virtual heritage conference

- Five of Stirling’s greatest John Allan buildings

- Women in Construction – Stirling event report

- Scotland’s trailblazing women architects

- Stirling’s Heritage: Spotlight on The Granary

- TBHC Scheme now open to properties in Dunblane and Blairlogie

- How drones help us inspect traditional buildings

- Hazardous Masonry & Masonry Falls

- Mason Bees: What’s the Buzz?

- Stirling Traditional Skills Demonstration Day Success!

- Floating Head Sculpture at Garden Glasgow Festival 1988

- The story behind Paisley Abbey’s Alien gargoyle

- Cambuskenneth Abbey

- Stirling City Heritage Trust Publications

- Sharing Memories: Taking '20 Great Buildings of Stirling' into the community

- William Wallace Statues In Stirling

- Coronations and Royal Christenings in Stirling

- The development of King's Park

- Energy efficiency project awarded grant from Shared Prosperity Fund

- Inspiring the Future: Stirling City Heritage Trust's Women in Construction Event at Wallace High

- Doors Open Days Talk: Who Built Stirling?

- 10 Years of the Traditional Buildings Health Check

- Growing up in Stirling: A Night of Reminiscence at The Smith

- SCHT visit to Brucefield Estate, Forestmill, Clackmannanshire

- Statement on Christie Clock

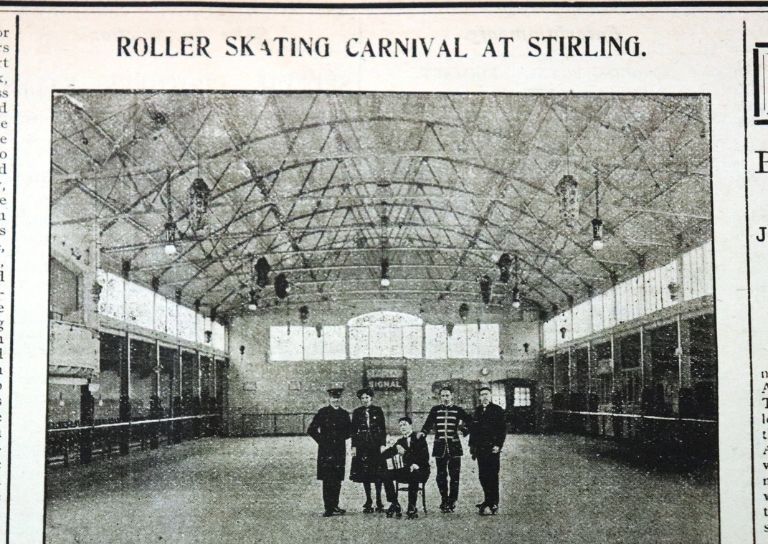

- Stirling’s Lost Skating Heritage

- Laurelhill House and the West Indies

- Beechwood House and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- About Us

- Support Us

- Contact

Christian MacLagan, a pioneering lady, but born too soon?

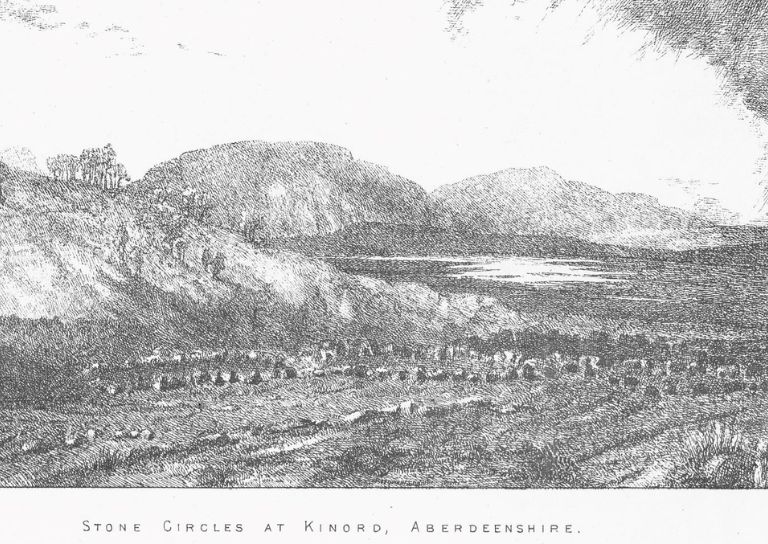

It’s 200 years ago – how do you study stone circles – if you’re a girl?

Christian was a very common girl’s name in 18th and 19th century Scotland, although now it’s used for boys. If Christian MacLagan had been born male in 1811, we’d never have heard of her. Christian is now well known as one of Scotland’s first, and most energetic female archaeologists. But (there’s always a ‘but’, isn’t there!) she’s definitely not ‘the very earliest’ or ‘absolutely the first’ woman to excavate, record and publish her findings. For instance, Alicia Spottiswoode (formally called ‘Lady John Scott’), was at work in Berwickshire in the early 1860s, several years before Christian.

Christian herself was blessed, and cursed with endless curiosity and the need to discover why the countryside around Stirling was full of ancient remains, from standing stones to the Roman Antonine Wall. This inspired her to become one of the Scotland’s first serious writers on prehistory (the period before the Roman invasions). Because women could not attend university, or even vote, she had to educate herself and became an insatiable reader.

Her late father’s distillery had gone bankrupt, and the MacLagans only had a small income. Christian’s widowed mother rented a cottage at Braehead (near Livilands Broch, now being investigated by Stirling Council’s archaeologist, Dr Murray Cook; see canmore.org.uk) in the 1820s. The family later moved to Edinburgh, but finances improved in the mid-late 1830s, when Mrs MacLagan’s brother, Thomas Colville, came back from India. Colville had made his own fortune in Bengal by growing and trading indigo, a ubiquitous and very profitable blue dye, used for thousands of Royal Navy uniforms.

How to spend a windfall – on your house

Christian and her mother were now supported by Christian’s two brothers, who joined the Colville indigo firm in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta). Christian was deeply religious and actively involved in the church – one of the few respectable outlets for socially-concerned women to try and help poverty-stricken working classes. She largely ‘disappears’ from our records, until her last brother left her his fortune in 1859, when she was 48. As a wealthy single woman, with no husband to bother her, she set about making her mark on Stirling.

Christian fitted all of the stereotypes used to describe lone female pioneers – ‘doughty’, ‘indomitable’, and ‘intrepid’. In modern terms, she was single-minded, supremely self-confident, stubborn, obstinate, and really rather brave. The Hays of Liverpool, architects who designed the Free North Church (now the Baptist Church, Murray Place), which Christian attended herself, and Stirling High School, seemed the obvious choice for her own large new villa – with 7 bedrooms! Unfortunately, Christian’s many talents also sometimes worked against her – she unofficially changed the builder’s instructions, and then sued the architects in 1861 when her own choices didn’t meet her previous ideas.

Spending more – legal cases are slow and expensive

The bad feeling this created meant she had to find a different architect for her small church (‘Marykirk’) in memory of her brother. Although nobody in Stirling had requested yet another church, Christian became obsessed with the project. She paid architect F T Pilkington, as eccentric as she was herself, for Marykirk’s plans. (Look at his bizarre, fairytale Barclay Viewforth Church, soaring over Edinburgh’s Meadows, here). However, she chose a steep, unsuitable site in St Mary’s Wynd, an overcrowded slum area. When the funding became a serious issue, she took the church officials to court. Christian showed real courage, and great perseverance, in her decade-long legal action, although it was misguided, expensive and unnecessary.

She could, and did, act ruthlessly, by evicting the Marykirk congregation, and literally taking the keys back. For a few years, in the 1870s, she provided the local newspapers with an endless saga, which readers took very seriously. The burgh council and Free Church were generally ‘against’ her, so she left the congregation and joined their rivals, the traditional Church of Scotland. They didn’t want the dark, damp building either, but were ‘persuaded’ to accept it, on condition she had no more involvement.

This was a public humiliation for Christian, but although we might see it as ‘a warrior woman against the all-male establishment’, much of the difficulty was down to Christian’s own character irrespective of her gender. She was very stubborn, and determined to ignore all advice when it contradicted her own fixed ideas. As we know from our own lives, refusing expert help often ends badly, as Christian discovered.

‘Ladies’ could vote – 50 years before we think they did

Everyone knows that women first got the vote in 1918 – or did they? What about the 1872 Education (Scotland) Act? This made primary schooling compulsory for all children for the first time. It’s little-known that it also allowed some (better-off) women to stand for election, and vote for the newly formed district school boards across Scotland. Christian’s name appears in a specimen, or ‘model’ (imaginary) voting paper, printed in the Stirling Journal in early 1873 to illustrate to the ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ how elections worked. She wasn’t an actual candidate, and probably didn’t give permission for her appearance, but it does show that she was a well-known public figure. In old age, Christian supported women’s suffrage campaigns, but she could have voted (and probably did) for influential education officials in every school board election for decades. (Other elected positions were added over time; more information at womenssuffragescotland.wordpress.com)

Travelling to ancient sites at last …

Christian next turned her restless energy to solving mysteries in the landscape, seeing ancient stones as holding information about their builders, and their original purpose. She tried to unlock this data by carefully drawing and measuring such sites, including hillforts, stone circles and duns (fortified round houses), all thousands of years old. She visited dozens of remote sites in person, climbing hills and crawling into Stone Age tombs – in long skirts. She began by sending short articles to the prestigious ‘Society of Antiquaries of Scotland’ in Edinburgh, and was recognised with a special honorary membership in 1871 (Alicia Spottiswoode was the first such ‘Lady Associate’, in 1870). She was very proud of this distinction, and used it after her name on her books and papers for ten years. Nowadays it’s been misinterpreted as a patronising snub, dismissing her as ‘a mere woman’, but it was a mark of deep respect by the standards of the time.

Christian knew she was more intelligent than many men, and grew frustrated when she couldn’t extend her knowledge by studying, as some (not all) private libraries didn’t admit women. Although she protested that she couldn’t join any historical societies, she was exaggerating. Stirling’s very progressive Natural History and Archaeological Society admitted women from its start in 1878. Christian wrote 8 papers for them – a considerable loss to the more sexist Society of Antiquaries in Edinburgh!

I’m still investigating Christian’s long life, and although there are no photographs of her, we can see traces of her in Stirling’s streets, her display at the Stirling Smith Museum, and her publications. She was a contradictory character, who fascinates 121 years after her death. Would she have made such efforts, and left her rich legacy of records, observations and folklore if she had been born male and life had been ‘easier’ for her – probably not. She rose to the problems she faced when entering conventionally all-male areas, such as church administration, or recording prehistoric monuments.

It’s hard not to admire her, even if, as a modern woman, I feel she might have been rather challenging to work with!

About the author

Morag Cross is an independent researcher and archaeologist, specialising in histories of buildings and land ownership. Her archival research explores the unexpected links between previously unknown figures, especially women, and their social networks. She has worked on over 80 projects including business histories for the Mackintosh Architecture website, Glasgow Council’s official WW1 website, M74 industrial archaeology research, and Edinburgh’s India Buildings, Victoria St.