- Home

- Our Work

- Stirling's Story

- Blog

- Women in Construction at Bannockburn House

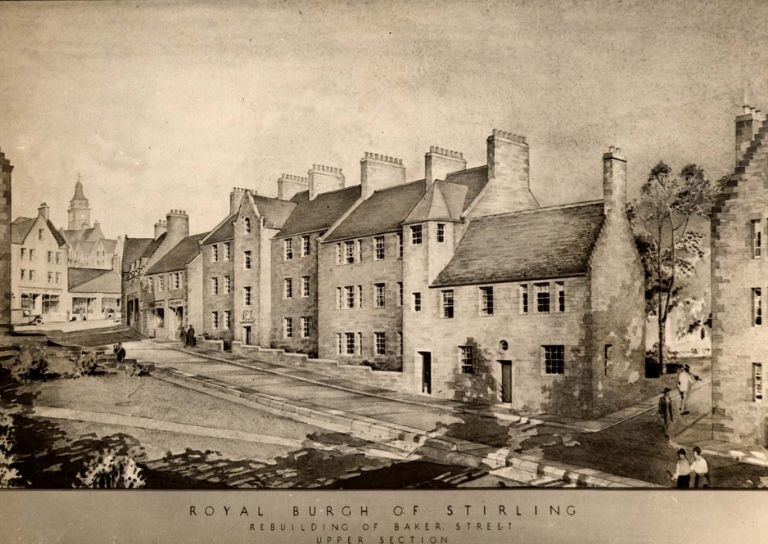

- Avenues to the Past: Stirling’s Historic Streets Exhibition

- Stirling Business Awards 2025

- What is a Conservation Area

- 20 Great Buildings of Stirling

- Reminiscence Art Project

- On the European Stage: Preserving by Maintaining conference, Bratislava

- The Abolition Movement in Stirling

- Practical Workshop on Retrofitting Insulation with A. Proctor Group

- Walker Family Visit

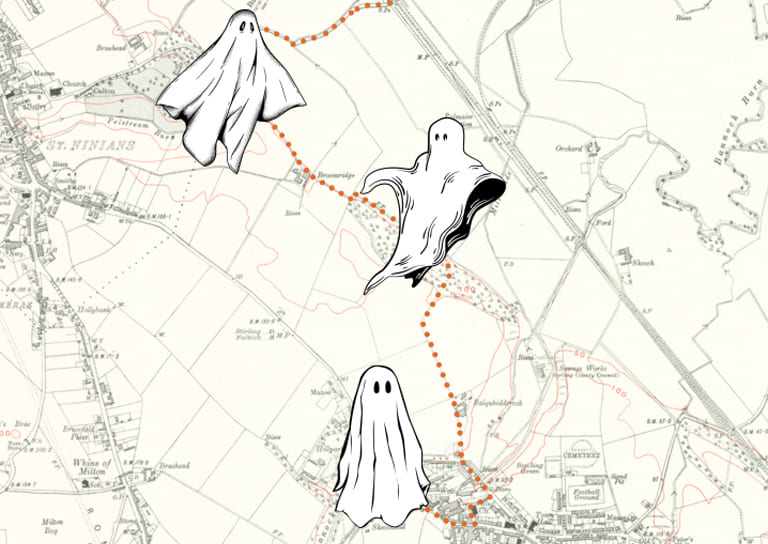

- Ghost Tales from Stirling

- Snowdon House and The West Indies

- Stirling’s Streetscape Stories: Photography Workshop

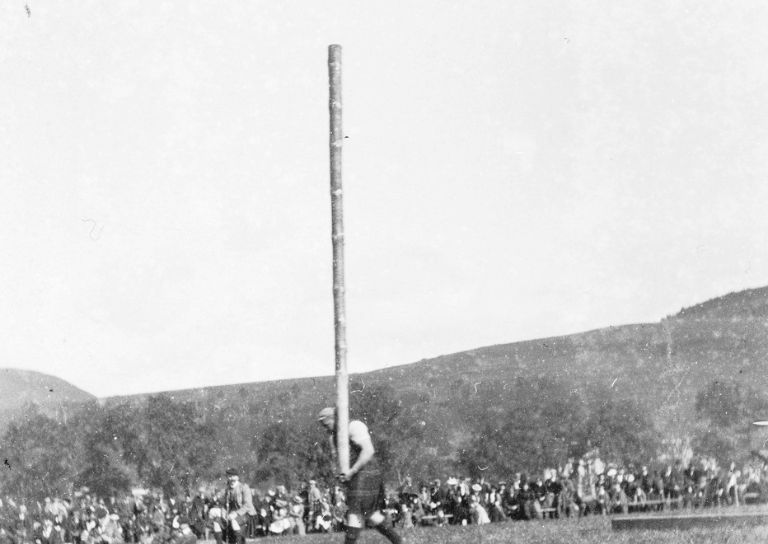

- Stirlingshire’s Highland Games

- Creative careers in the heritage sector

- Postcards From Stirling

- Stirling’s Gala Days

- Building Surveying Student Intern at Stirling City Heritage Trust

- Heritage Trail: Stirling Walks

- Local History Resources

- Stirling Through the Decades

- Stirling’s STEM Pioneers

- Traditional Skills: Signwriting

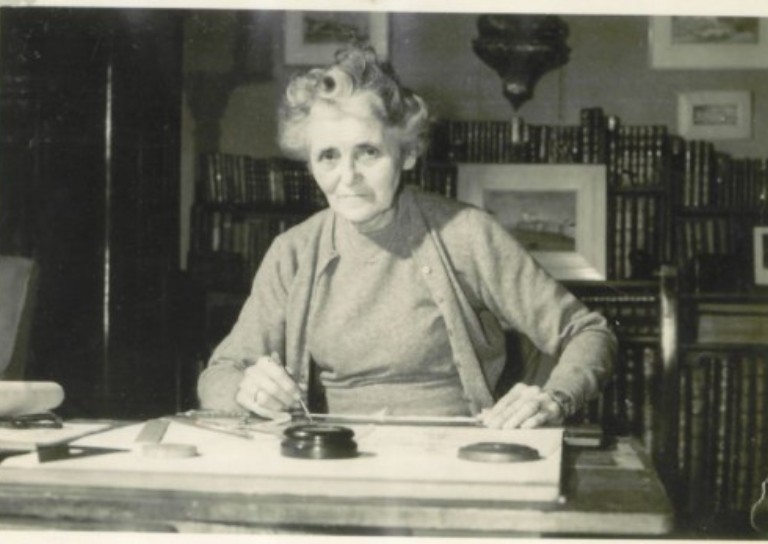

- Christian MacLagan, a pioneering lady, but born too soon?

- Traditional Shopfronts in Stirling

- Stirling History Books for World Book Day

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Joe Hall

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Lindsay Lennie

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Andy McEwan

- My Favourite John Allan Building by Pam McNicol

- Celebrating John Allan: A Man of Original Ideas

- The Tale of the Stirling Wolf

- Stirling: city of culture

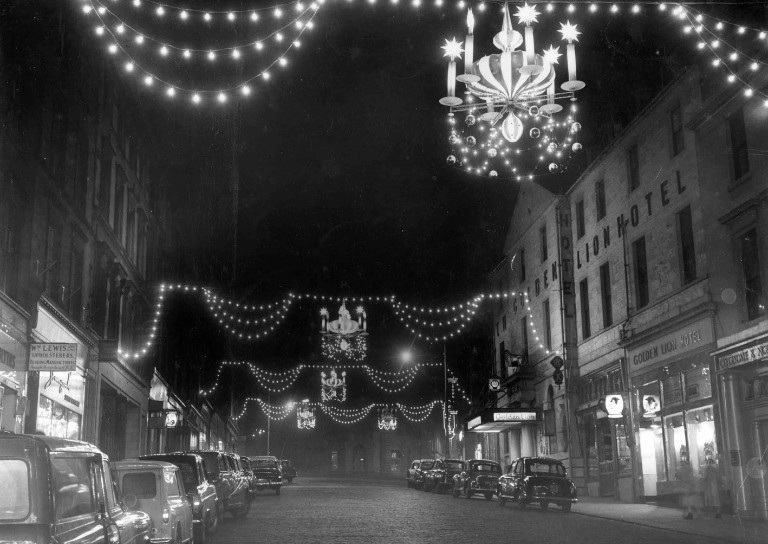

- Christmases Past in Stirling

- Stirling’s Historic Graveyards

- Top 10 Tips for Architectural Photography

- An Interview with David Galletly

- Springtime in Stirling

- The Kings Knot – a history

- A Future in Traditional Skills

- Robert Burns’ First Trip to Stirling

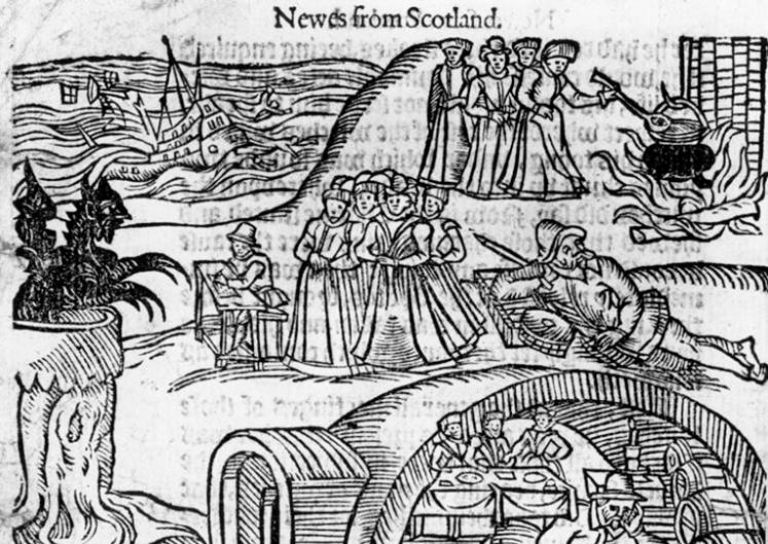

- Stirling’s Witches

- Stirling’s Ancient Wells

- An architecture student’s take on the City Of Stirling

- Ronald Walker: Stirling’s Architect

- Stirling’s Statues

- Stirling’s Wee Bungalow Shops

- Stirling’s Historic Hospitals

- Women in Digital Innovation and Construction

- Heritage at home: 8 of the best online heritage resources

- Stirling featured at virtual heritage conference

- Five of Stirling’s greatest John Allan buildings

- Women in Construction – Stirling event report

- Scotland’s trailblazing women architects

- Stirling’s Heritage: Spotlight on The Granary

- TBHC Scheme now open to properties in Dunblane and Blairlogie

- How drones help us inspect traditional buildings

- Hazardous Masonry & Masonry Falls

- Mason Bees: What’s the Buzz?

- Stirling Traditional Skills Demonstration Day Success!

- Floating Head Sculpture at Garden Glasgow Festival 1988

- The story behind Paisley Abbey’s Alien gargoyle

- Cambuskenneth Abbey

- Stirling City Heritage Trust Publications

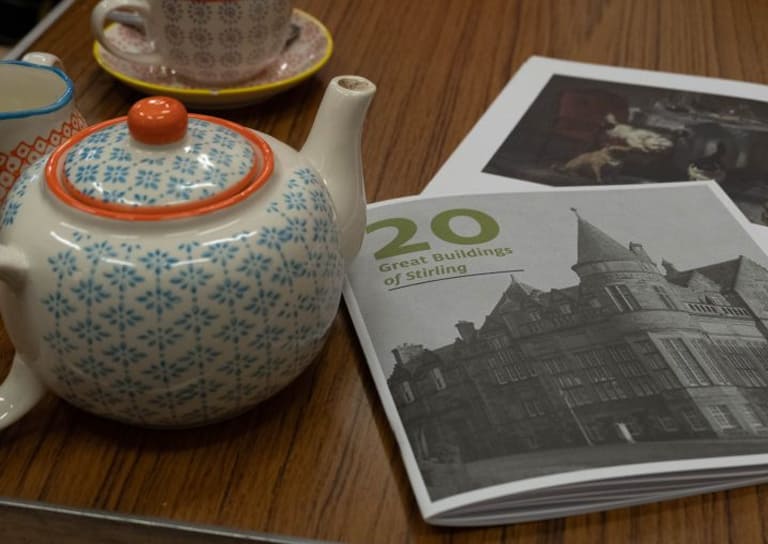

- Sharing Memories: Taking '20 Great Buildings of Stirling' into the community

- William Wallace Statues In Stirling

- Coronations and Royal Christenings in Stirling

- The development of King's Park

- Energy efficiency project awarded grant from Shared Prosperity Fund

- Inspiring the Future: Stirling City Heritage Trust's Women in Construction Event at Wallace High

- Doors Open Days Talk: Who Built Stirling?

- 10 Years of the Traditional Buildings Health Check

- Growing up in Stirling: A Night of Reminiscence at The Smith

- SCHT visit to Brucefield Estate, Forestmill, Clackmannanshire

- Statement on Christie Clock

- Stirling’s Lost Skating Heritage

- Laurelhill House and the West Indies

- Beechwood House and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings

- Building Resilience: Maintaining Traditional Buildings

- Shopping Arcades

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Fabric First

- Stirling Reminiscence Box

- Level 3 Award in Energy Efficiency for Older and Traditional Buildings Retrofit Course (2 Day)

- New Retrofit Service now available for Traditional Buildings Health Check Members

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Windows

- Architects and The Thistle Property Trust

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Insulation

- Stirling City Heritage Trust at 20

- Miss Curror and the Thistle Property Trust

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Chimneys

- Statement on Langgarth House

- World Heritage Day: Exploring Hayford Mill

- Retrofitting Traditional Buildings: Climatic Adaptation

- SCHT 20: Championing Women in Construction

- Guest Blog: Dementia Friendly Heritage Interpretation

- Community Consultation launched for Stirling’s Heritage Strategy

- Stirling's Lost Swimming Pools

- SCHT Grant Conditions: Owners Associations

- Kings, Wolves and Drones: 20 years of care and repair at Stirling City Heritage Trust

- SVE Inspire Awards September 2024

- Women in Construction at Bannockburn House

- About Us

- Support Us

- Contact

The Abolition Movement in Stirling

This Black History Month we have decided to explore Stirling’s lost heritage and its links with the Abolition Movement and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. All of the buildings we’ll be exploring have been demolished, but that doesn’t mean their role in Stirling’s history should be forgotten. Their legacies often live on in modern place names, as well as in photographs and newspaper articles.

Stirling is not a port city, so you might be surprised to learn that the city’s wealth and built heritage has links to the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Men who had made their fortunes through the slave trade settled and built their impressive houses in Stirling throughout the 19th century. However, whilst some of Stirling’s residents owned enslaved people until the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1833, others, including the Guildry of Stirling, had been demanding the abolition of the slave trade since 1792, stating unanimously that: ‘the practice of kidnapping and buying slaves on the coast of Africa and afterwards exposing them to sale is contrary to the inherent laws of humanity and repugnant to those principles of justice and civilization which are the reputed characteristics of the British Constitution’.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, many Scots were involved in the Abolition Movement, with churches acting as important hubs, locally and nationally, for the movement. North Parish Church in Stirling town centre was one of these hubs. This Norman and Romanesque inspired church opened for worship in 1842 but was demolished in 1969, and the site is now home to the Thistles Shopping Centre. Thankfully, Stirling Archives hold a wonderful collection of postcards, many of which show Murray Place and the church before the Thistles Centre was built. The Archives also hold a variety of records for North Parish Church, including kirk session minutes. If you would ever like to go in and have a look at these, you can book an appointment online.

On Thursday 9 May 1861, The Stirling Observer reported on ‘a most interesting lecture’ delivered by Rev. M. Johnson at North Church. Rev. Johnson had been enslaved on a plantation in Kentucky until he managed to escape, making him a fugitive. If caught, he would have been returned to his ‘owner’. At the time of the Lecture, Johnson had just completed 4 years of medical and theological studies at the University of Edinburgh, as he wanted to become a doctor and eventually travel to Africa as a missionary.

Just a year or so before Rev. Johnson gave his lecture in Stirling, the last known slave ship to bring captives from Africa to the United States, arrived at Mobile Bay. After this voyage, the ship was scuttled by its owner in an attempt to destroy evidence, because the importation of slaves to America had actually been illegal since 1807/8. On February 8 1861, mere moths before Rev. Johnson’s lecture, seven slave states had seceded from the United States of America to form the Confederacy, and as a result the American Civil War began on April 12, 1861.

A Stirling Observer journalist reported on Rev Johnson’s incredible story, some of which we’ve transcribed below:

He alluded in feeling terms of the conflicting emotions he felt before he made up his mind to flee from the plantation in the States where he had been a slave; his master had been an exception to many overbearing slave-owners; he feared on the one hand that his owner might die, and he might be transferred to the hands of a tyrannical slave-dealer; again there was the prospect that by his death he might make his escape.

He described the affecting parting from his sister, and the obstacles met with by the negro in making his escape owing to the presence of venomous reptiles; the crossing of swamps, rivers and mountains, all of which had to be overcome by dauntless perseverance, patience and courage.

He referred to the great advantage the North Star was to the fugitive slave in guiding him northwards to the Canadian frontiers, the land of freedom, and gave a graphic account of the obstacles successfully overcome by Mr Torry in the organisation of means for the formation of the underground railroad, describing its origin and complete success, with the facilities it afforded to the negro in making his escape, and hastening and completing his emancipation from bondage.

The lecturer, who occasionally broke out in burts of eloquent declamation, was listened to throughout with close attention and deep interest.

Although many people were Abolitionists, the road to emancipation was long and difficult, as so many British people had financially benefitted from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, and were integral to its development. The Royal African Company was founded in 1660 and went on to ship more Africans to the Americas than any other company in the history of the Atlantic Slave Trade, and was owned by the British Crown. By 1688 Quakers in Belgium and Germany were already opposing slavery, and encouraged British Quakers to take up the cause.

The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, which abolished slave trading throughout the British Empire, was passed in 1807 following years of campaigning by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, est. 1787. Unfortunately, this did not put an end to slavery. In 1833 The Slavery Abolition Act was passed, which set out a gradual plan to abolish slavery throughout most of the British Empire over 6 years. In 1838 all enslaved peoples in British colonies were freed after a period of forced apprenticeship, and the British and foreign Anti-Slavery Society was founded to outlaw slavery in other countries. It is the world’s oldest international human rights organisation, and still operates as Anti-Slavery International.